History of Darjeeling Tea - the German Connection ~ Part 2

The Wernicke-Stolke Tea Enterprise

One day in 1888, accompanied by his two little boys, Andrew Wernicke went down to Pandam tea estate, located below Darjeeling town on the northern slope. He had just bought the “rifle range” part of the estate. Upon arrival at the factory some old workers asked Andrew Wernicke for a sign by which they might recognize him as the new owner. Wernicke reached for a branch of a nearby tree and broke it. “This simple procedure was enough to satisfy them,” recalled one of the sons later.

Andrew Wernicke was the second generation of Wernickes who had arrived in Darjeeling nearly 46 years ago as Baptist missionaries. Andrew was the son of Sophie Wernicke and Johann Andrea Wernicke. He was only a few months old when the family moved to Darjeeling. At the time of the Pandam tea estate purchase Andrew was 48 years old, and owner of several tea gardens already.

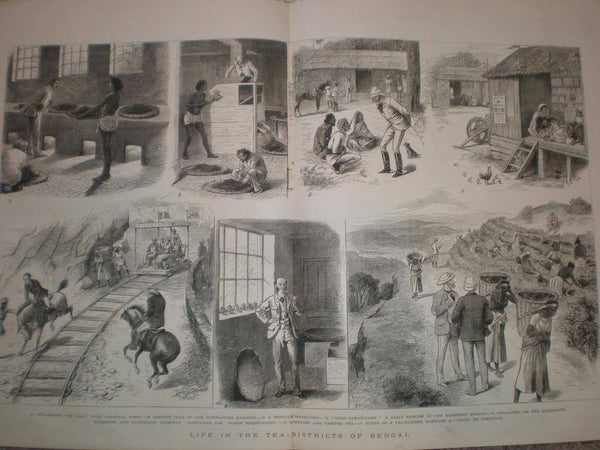

A tea planter’s life has never been easy; for the pioneers it was an uphill battle. Apart from the monumental physical labor, the planters in the early years of the Darjeeling tea industry had only a rudimentary knowledge about the cultivation and manufacture of tea, none first hand, to work with. They had to learn everything on the fly and on their own. Besides tending to the plants, they also had to know about machinery, construction and manage a labor force that had no idea about organized work.

A few Chinese workers from the “original tea country”, recruited by the famous “plant thief” Robert Fortune, were brought in to assist but their numbers were few, and their depth of knowledge questionable.

Due to the remote locations of tea gardens, the planters were usually cut off from their families and also from other planters precluding “quick consults.” It also meant construction had to be carried out with materials found at site. In the early years the factories and bungalows were no more than roughly built sheds of mud and stones with thatch roofs.

Andrew Wernicke started his career in 1864 as a 23 year-old-assistant to Captain Masson at Tukvar Tea Estate. He worked there for three years, planting out the 4th division of the garden, which was considered one of the best divisions in Darjeeling for a long time. In addition to Tukvar, Andrew took charge of Makaibari tea estate towards the end of 1865. It is extraordinary how he could manage these two gardens, separated by at least 25 miles (the construction of the arterial Hill Cart Road was underway at this point).

But that was a small accomplishment against what he was to attain two years later. In 1867 Tukvar and Makaibari were the first tea gardens of Darjeeling to report profit, thereby removing all doubts of whether the “tea experiment” would work in Darjeeling. It came at a time, Wernicke’s obituary would later recall, when “old planters like Mr Halifax and Mr Harold had actually withdrawn for a time in despair of success in the hills.”

Andrew was not the first in his family to join the tea industry. His brother, Fred Wernicke, two years younger had joined Soom tea estate as assistant to Capt. Jerdon, a year before him in 1863. Fred’s story is low-key compared to Andrew’s but he seems have been a remarkably affable man. “In Darjeeling Planting - Then and Now,” an essay by Lt Col L Hannagan (the date of the writing is yet to be ascertained), an incident involving Fred Wernicke is recorded that shows he was ready to cross the cultural borders that lay between the colonists and natives.

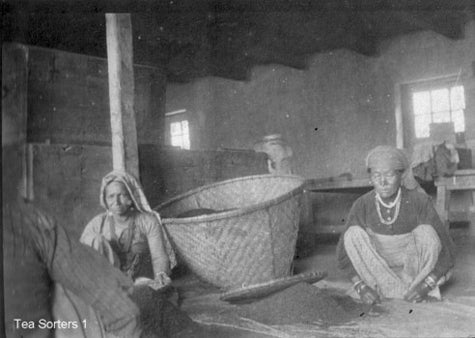

“On many an occasion, he (Fred Wernicke) would be joined by one of his teamakers who was having a few minutes rest from his work, and they would sit side by side discussing the work or village problems. On one occasion, a friend who suffered from over-rated sense of his own importance, and never permitted such “liberties,” was horrified when a teamaker came out, sat down by Fred Wernicke, put his arm around his shoulder and gave him an affectionate hug, and addressed him as “Daduu” (perhaps daju? which means older brother) or brother.”

Fred’s uncharacteristic gesture seems to reflect the way in which the Wernickes and Stolkes embraced Darjeeling. Nearly three generations of these Germans lived (and many died) in Darjeeling. One of Andrew’s cousins even took a local Lepcha woman as his “wife.” But more of that later.

Next week: The Wernicke-Stolke Tea Enterprise continues.

History of Darjeeling Tea - the German Connection ~ Part 1